Bunch, Marlee S. Unlearning the Hush: Oral Histories of Black Female Educators in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2025.

Introduction

In her remarkable book, Unlearning the Hush: Oral Histories of Black Female Educators in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era,[1] Marlee Bunch traces the stories of Black teachers who lived and worked during the eras of segregation and desegregation in Mississippi, transforming the geography of educational history into a geography of resistance. Rooted in oral histories, archival fragments, and Black feminist theory, Bunch reframes our understanding of the intersections of race, gender, and pedagogy.

Her book explores what we have failed to hear rather than focusing on recovering the lost voices. The writer reasons that silence is not neutral and explores how Black women educators endured silence, both physically and methodically. Ultimately, they are confronting the “hush” as both a literal cultural phenomenon of imposed silence and a metaphor for the institutional constraints shaping teacher education. Bunch constructs a history that not only preserves but also serves as a corrective. Through the voices of Black teachers, the book challenges the reliance on administrative archives and policy narratives to define educational change.

Geographical and Educational Landscapes

Setting this book in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, a city shaped by Jim Crow and massive resistance, is deliberate. Historically known for racial violence and education disparities, Mississippi’s geography shaped desegregation and memory. Schools were central to community life, and their desegregation caused a profound cultural rupture. Rural Delta’s isolation and poverty worsened the consequences of policy changes that closed Black schools. These closures disrupted education, community networks, mentorship systems, and care infrastructures. The landscape, with its quiet fields and vanishing schoolhouses, communicates loss and resilience.

The intersections of social and physical landscape in Mississippi highlight that geography and history collectively produced both educational inequalities and the movement to transform. How Black educators transformed Mississippi into a hub of extraordinary intellectual labor is evidence of the devastating impact of racial terror and segregation. These oppressive systems led to the creation of learning spaces that transformed the act of teaching into a political act, fostering self-worth and civic consciousness among the Black community.

Positionality and Methodology

Bunch’s commitment to reciprocity and reflexivity, as a Black woman researcher, gives the book emotional power. Her interviews with Black educators show that desegregation, which was supposed to be a step forward, actually created new problems. Black teachers were pushed out of their jobs, their teaching methods were ignored, and their stories were completely forgotten. Bunch uses oral history to bring these forgotten places back to life, showing how memories live on in stories shared over kitchen tables and church gatherings. By doing so, she transforms the archive, making history alive, spoken, and emotionally charged.

Methodologically, Bunch’s work exemplifies oral history as a research tool and a relational practice. Drawing from Black feminist epistemology, she treated Black women educators’ stories as primary evidence, not mere anecdotes, through extensive interviews spanning generations. Bunch’s participants, Black women teachers, taught in various settings, from segregated Black schools to freedom schools and later in desegregated institutions where they were often the sole Black educators. Their classrooms varied from formal public schools to church basements and community centers. Additionally, they taught a diverse range of subjects, including literacy, mathematics, art, citizenship, and self-love. They blended religion, civic education, and a strong belief in Black children’s potential. In classrooms with peeling walls, the purpose was clear. They made freedom a tangible reality. These spaces were also not just sources of knowledge but models of resistance where learning exceeded academic achievement and fostered respect and resilience in a world that oppressed them.

Through their narratives, Bunch presents a hidden map of educational practice that defies easy categorization. She shows how these spaces, often constructed with limited resources, have emerged as incubators for political awareness. Her narrative draws inspiration from the tradition of “fugitive pedagogy” as described by Jarvis Givens, but also expands it into the contemporary teacher education program. She contends that these women were not only educators but also theorists, as their daily routines constituted a personified curriculum of care, authority, and transformation.

Findings and Lessons

At its core, the book argues that silence was a survival strategy and constraint for Black women educators. Their stories reveal how teaching became a quiet rebellion. It was a form of activism through persistence, navigating respectability politics, institutional neglect, and racial isolation. Participants used humor, faith, and community to sustain themselves.

Bunch’s findings also shed light on the dual nature of teacher education, revealing that it simultaneously disciplines voices and, paradoxically, fosters resistance. Bunch urges institutions to reconsider teacher preparation through a historical lens, advocating for programs that genuinely honor the epistemologies of Black women educators rather than merely including them in diversity statements. Bunch’s work has important implications for teacher education, positioning it as a contested site of knowledge production shaped by historical silencing, institutional power, and Black women educators’ intellectual labor.

The book contributes to a growing body of scholarship that re-centers Black women’s intellectual histories in education. This scholarship extends the narrative arc begun by Givens’s Fugitive Pedagogy and Vanessa Siddle Walker’s Their Highest Potential, while also intersecting with Elizabeth Todd-Breland’s A Political Education.[2] However, Bunch distinguishes herself by focusing on teacher education as a contested site of knowledge production, rather than solely on classroom instruction.

The author’s integration of oral history and feminist theory positions Unlearning the Hush within a methodological shift in educational historiography that emphasizes affect, embodiment, and relational archives. By doing so, she expands the definition of evidence and encourages readers to approach narratives as theoretical constructs rather than mere testimonies.

Lastly, Bunch’s participants leave a legacy of intellectual and moral courage, reminding us that teaching is a moral calling shaped by context, community, and conscience. Their “unlearning the hush” becomes a metaphor and mandate for educators to name silencing systems, honor whispered labor, and build classrooms for honest dialogue. Furthermore, in the current moment of renewed attacks and politicization on teacher education, Unlearning the Hush emphasizes the inseparability of the struggle for educational justice with narrative control. Bunch’s work demands we reconsider who tells the story of American education and whose voices remain unheard.

Further Questions

Bunch incorporates historical context and visual materials while deliberately centering oral histories over administrative or policy archives, foregrounding lived experience rather than institutional analyses of how state or district policies shaped Black women educators’ lives. Readers seeking extensive quantitative data or detailed policy analysis may find that the book prioritizes narrative and memory over statistics. This, however, is a deliberate methodological choice that reflects Bunch’s commitment to honoring lived experience without becoming overdetermined by bureaucratic frameworks.

Future researchers could build on Bunch’s work by comparing Mississippi’s story with that of other Southern states or by examining how the “hush” continues to operate within contemporary teacher education programs. The book’s conceptual framework is both flexible and adaptable, offering a compelling lens for studying silence, agency, and teaching across varied educational contexts.

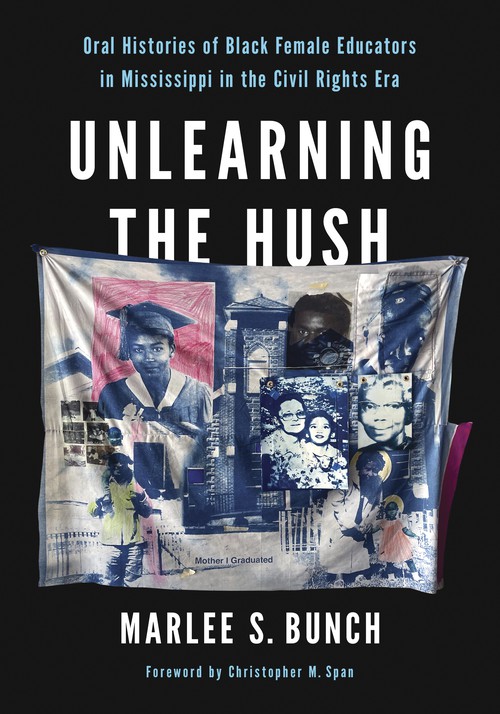

I found that the inclusion of photographs, visual artwork, and poetry deepens the book’s affective register, reinforcing Bunch’s argument that memory and meaning exceed textual archives. However, I do feel that the density and interpretive richness of these materials are so extensive and attention-grabbing that they merit a separate, focused, and compassionate review by someone who is able to relate with them via experiences, or must I say, their own stories.

Conclusion

Marlee Bunch’s book transforms silence into scholarship. Unlearning the Hush contributes to Black women’s education history and demonstrates how history can listen. Through geography, memory, and voice, Bunch reveals the classroom as a powerful site of resistance in American life. Historians of education find inspiration and challenge in her work, which is to write breathing history, honor lived experience, and unlearn disciplinary hush.

Footnotes

[1] Marlee S. Bunch, Unlearning the Hush: Oral Histories of Black Female Educators in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2025)

[2] Jarvis R. Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021); Vanessa Siddle Walker, Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); Elizabeth Todd-Breland, A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

Bibliography

Bunch, Marlee S. Unlearning the Hush: Oral Histories of Black Female Educators in Mississippi in the Civil Rights Era. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2025.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Givens, Jarvis R. Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Todd-Breland, Elizabeth. A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Walker, Vanessa Siddle. Their Highest Potential: An African American School Community in the Segregated South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to Dr. Velazquez for introducing me to Unlearning the Hush and to Dr. Ransom for her thoughtful feedback and encouragement throughout the development of this review. I also extend my appreciation to Dr. Marlee S. Bunch for her scholarship, which made this reflection possible.